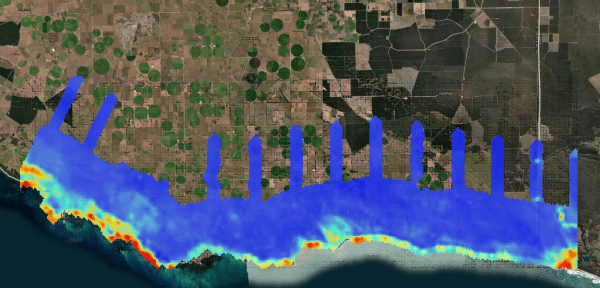

The new research project Adaptation of the South-Eastern drainage system under a changing climate has kicked off its fieldwork program with an airborne electromagnetic (AEM) survey along the coastline south of Mount Gambier.

The project began last month and will help the Limestone Coast Landscape Board determine whether there are opportunities to manage water from the extensive drainage network in the region to address risks to primary industries and groundwater dependent ecosystems. It is part of the Limestone Coast Landscape Board’s broader water resource management approach of ‘Making Every Drop Count’, which has funding support through the National Water Grid Authority (NWGA) Science Program, NWGA Connections Funding Pathway and the South Australian Governments Landscape Priorities Fund.

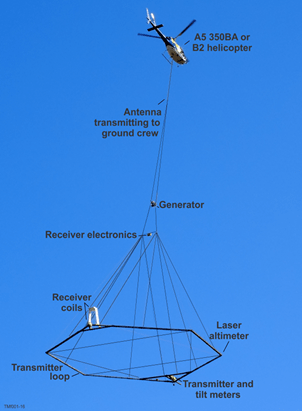

The project is being delivered by the Goyder Institute, with CSIRO recently using a low-flying helicopter carrying a long circular frame to collect information as it flew in parallel lines across the coastline and inland. A total of 1277 km were flown, with the local community kept informed about the fieldwork by the Limestone Coast Landscape Board.

Airborne electromagnetics (AEM)

AEM techniques were developed specifically for land and groundwater assessment, and to help understand if and how surface water and groundwater move from one to the other in the landscape. This technology is being used to help assess the quality of the water contained in the ground and to help map how far salt water from the ocean has moved into the coastal groundwater systems.

A helicopter AEM system is a quick and cost-effective method to map the area along the coast as it can provide detailed information in a very short period of time.

How do helicopter AEM systems work?

The AEM system used measures the changes in conductivity (an indicator of salt level) of the ground. Helicopter AEM systems carry transmitter and receiver coils mounted in a frame that hangs beneath the helicopter. A weak electrical current goes through the transmitter coils. The current in the coil makes small, temporary currents in the ground, which in turn make small, temporary magnetic fields in the ground and these are detected in the receiver coils hanging beneath the helicopter. If the groundwater changes (if it is deeper or more salty), the magnetic field signals will change. Changes in the magnetic field help to map the groundwater and subsurface better.

Please contact Daniel Pierce, Research Project Manager, Goyder Institute for Water Research, for more information about the project or the Institute’s research program.